04 Jul 2019

Health researchers: Which “Deadly” are you?

First Nations woman, Amy Creighton, asked a room of infectious disease researchers to make sure they are the right kind of “Deadly” before even beginning to become involved in research with First Nations people.

For many First Nations people, deadly has the opposite meaning to the widely accepted negative one – it means excellent, very good or awesome. Part of becoming the positive “Deadly” is to better understand experiences of racism and the power imbalance in Australia and how this impacts First Nations research.

The researchers were attending the Minya Cultural Respect Education (Minya) workshop in May, delivered by First Nation Gomeroi Murri’s Amy and Garry Creighton for the Australian Partnership for Preparedness Research on Infectious Disease Emergencies (APPRISE) Centre of Research Excellence.

The development of Minya has included extensive consultations and negotiations with First Nations peoples and health research professionals. As a result, Minya is a living program that is continually revised.

The sessions challenged researchers to understand their personal and professional behaviours and attitudes, and how these can influence research practices. Minya promoted understanding around creating space to centre and privilege First Nations voices in research.

Amy, a Gomeroi Murri Yinarr (First Nations woman) and Aboriginal Program Manager at Hunter New England Population Health in NSW, said it is fundamental to First Nations research that researchers use culturally safe research practices defined by First Nations people.

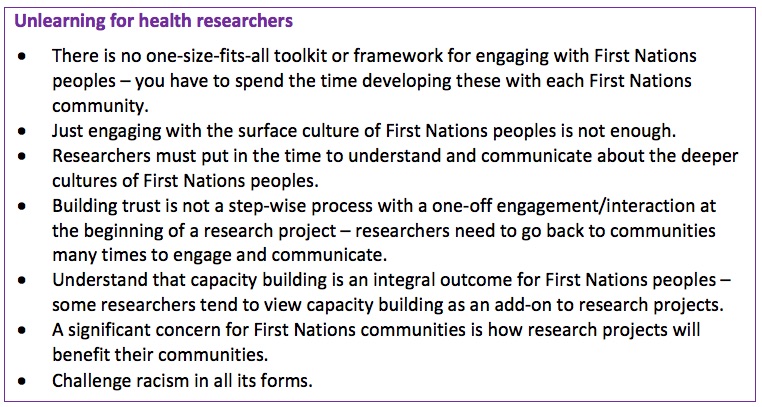

Becoming a deadly researcher through unlearning

The concept of unlearning featured over the day and a half. For researchers, unlearning begins with talking less and creating space for truths to be told – for First Nations people to be listened to and to be respected. This provides an opportunity for researchers to focus on looking, listening (winangali) and learning about First Nations peoples lived experience of culture, connection and country. Only when this occurs might researchers begin to understand and address the barriers that will hinder culturally safe research practices.

Once workshop participants had listened, Amy asked them to begin talking (guwaali). This included unpacking racism and understanding its impact. The activity of making racism visible provided an opportunity to realise the relentless, daily racism experienced by First Nations people.

“Understanding racism and the impact of past culturally unsafe research practices can help researchers understand why First Nations people may be hesitant to engage with researchers – the past, the present and the future are so intrinsically intertwined,” Amy said.

Garry stressed the importance of spending time with First Nations people.

“We are the most researched people in the world. People love researching us,” he said. “You want to know about us, but you don’t want to know us…you have to go deeper.”

Changing the way researchers do business – focus on outcomes for communities

Non-First Nations people tend to interact with surface aspects of First Nations’ culture and community, the top of the cultural iceberg – food, flags, Welcome to Country, fashion, art and music.

Amy stressed that to positively impact on the health of First Nations communities, researchers must improve their understandings of deeper cultural elements such as communication style, attitudes, beliefs and cultural nuances. A less individualistic perspective on self and family is central to understanding First Nations concepts of health, as is a need to respectfully consider both past and future.

An important element of engaging more deeply with communities is focussing on tangible community outcomes such as job creation or skill development, which are typically only small components of the research process.

Amy and Garry stressed that an increased focus on community outcomes is a main contributing factor in improving First Nations health outcomes.

Another useful approach can be the use of qualitative stories to generate change for First Nations peoples.

First Nation’s people have often been spoken of in the deficient, but “all our stories tell me we are strong,” Amy said. “How can you survive what we’ve endured without being strong? We need to reframe and focus on the strength of our communities and build this into research.”